6. Were the Beatles ‘used as propaganda’?

The group were surprised to find that the Greek media were apparently being kept informed of their itinerary

One might assume that the authoritarian Greek junta that had come to power in 1967 wouldn’t want to associate itself too closely with the Beatles. After all, the regime soon made clear its deep cultural conservatism and clashed with various music and film stars who held progressive views.

According to the historian Effie Pedaliu, even the Beatles’ own song ‘She Loves You’ was put on the junta’s list of forbidden culture:

“Greek citizens were forced to abide by an endless list of preposterous prohibitions including bans on gatherings exceeding five people, wearing one’s hair long or listening to certain musicians and kinds of music including, among others, Tchaikovsky, Dvorzak, and the Beatles’ ‘She Loves You’.”1

Dr Pedaliu told me: "My supposition is that the problem was long hair and that the lyrics contained the words 'Yeah! yeah! yeah!'. In Greece at that time, the 'Yeah-yeahs' (yeyedes in Greek) was a synonym for hippies."

The junta tended to see big pop and rock bands as corrupting influences on young people. In this light, a London newspaper report2 while the Beatles were in Greece claiming that any attempt by the group to establish a base in the country would be “likely to be blocked” would seem reasonable enough. “My information from Athens is that the military regime there will do nothing to encourage the kind of young, liberal-thinking visitors whom the group might attract,” said the article’s writer.

In fact, this information was inaccurate. It seems that Greek officials actually encouraged publicity about the Beatles’ trip, in the hope that this might help revive the country’s flagging tourism industry.

The disruption and negative publicity caused by the colonels’ recent coup had hit tourism, which was an important and previously growing part of Greece’s economy. A Financial Times article on 13 July reported on the “depressing picture” facing the country’s tourism sector: “semi-officially”, it said, total annual earnings were predicted to be $20-25m lower than anticipated, with anecdotal evidence suggesting that even this was “over-optimistic”. The writer commented:

“The fact that Colonel Balopoulos, one of the hard-core members of the military leadership which organised the coup, has been placed in charge of the National Tourist Office is an indication of the importance the regime attaches to this sector.”

Media reports at the time (many of which are collected at King’s College London’s Modern Greek Archive) recorded how the junta was making significant efforts to attract tourism. At the end of June, a reception held by the Chamber of Trade and Industry of Athens at the Cafe Royal on London's Regent Street was interrupted by 40 demonstrators, reported the Guardian.

The event's host Christos Michalos "made an impassioned plea for British tourists to come to Greece", said the newspaper. "It seems that Mr Michalos has been primed by the Greek government to appeal for normal conditions in the tourist trade and trade in general.” The article explained:

"One result of the military takeover in Greece has been a sharp decline in the country's tourist trade. The Colonels are naturally worried."

The Greek government had been at pains to correct impressions that it was discouraging certain types of visitor. In May 1967, the New York Times reported that Greece issued an order banning tourists with long hair or beards from entering the country, as well as those that were "clothed in rags or slovenly dress" and any with less than $80.

But the junta issued a statement in London the following week saying it was "utter nonsense" that everyone with long hair or a beard would be banned: only the "dirty and unkempt" needed to worry. The Daily Telegraph, which reported the announcement, also quoted the director of Greece’s National Tourist Organisation saying: "Visitors are welcome to Greece as they have always been, and it is only the occasional unpleasant, unclean type of Beatnik that we object to.”

Media anticipate Beatles’ movements

Given such anxiety about tourism, it’s striking that some of the Greek media seems to have been kept informed about the Beatles’ movements. Before beginning their island-hopping cruise, the Beatles spent a few days visiting Athens and nearby areas. The Times reported3 that on 23 July, the group quickly changed their mind about attending a performance of a Greek tragedy at the ancient sacred site of Delphi:

"The Beatles' outing, which had been given wide publicity by Athens Radio, did not come off too well. The Beatles drove up to Delphi, but when assailed by the crowds, and persistent journalists, they reentered their cars and left for Athens immediately.”

Several writers indicate that scenes like this were not unusual – and arose through the actions of Greek officials. Alistair Taylor4, (the Beatles’ “Mr Fixit” who was on the trip) recalls that “someone kindly told the Greek tourist board of our movements and everywhere we went there were hordes of fans”.

And in his 1968 authorised biography of the Beatles, the journalist Hunter Davies writes that when visiting Greece the group were asked by an official to visit a “quiet little village”. Upon arrival they “found hordes of press and TV people. It had all been organised by the tourist people, who used the Beatles as propaganda.”

The Greek media’s interest in the Beatles’ trip is apparent from photographs, still available commercially, that show the group arriving at the airport in Athens and standing alongside local musicians at Arachova, a village near Delphi. Some of these were taken by the Greek photojournalist, Aristoteles Sarrikostas – as Sarrikostas, who was then working for the Associated Press, recalled to the Greek website News 24/7 in 2017.

The photographer claimed that the Beatles' "agent" had informed him of the group's arrival in advance, so he could snap them at the airport, asking him to be "as discreet as possible". Two days later, Sarrikostas photographed the group at Arachova, after the "agent" had called him again and told him to come to the town “as quickly as possible". "I really praise God that I managed to take this photo, which went around the world through the Associated Press," said the photographer.

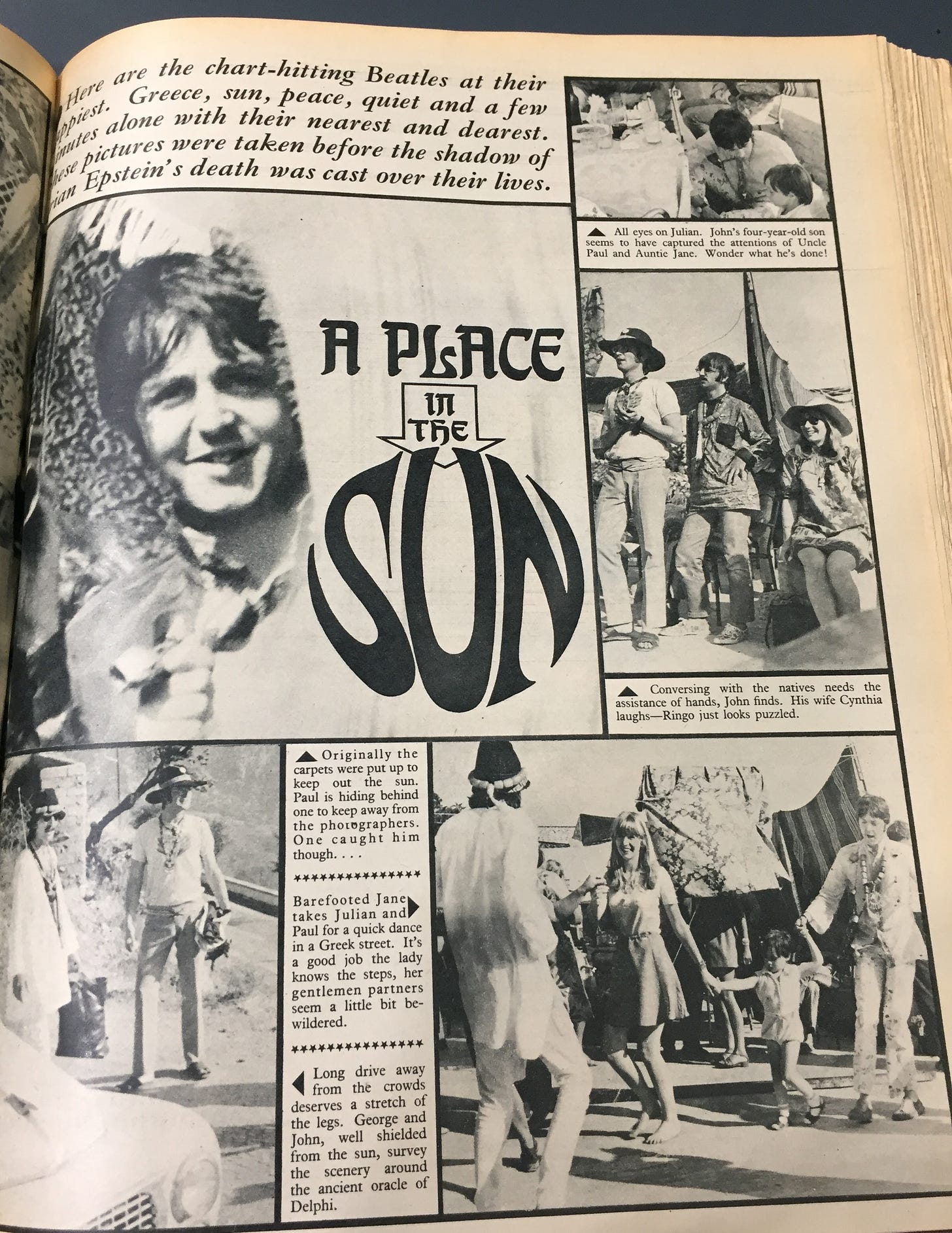

And Sarrikostas wasn’t the only person taking photographs of the Beatles. By whatever route, pictures of them certainly reached the UK pop magazine Fabulous 208. The publication’s October 1967 edition carried a double-page spread with the title "A Place in the Sun", and photos of the Beatles in Greece. "Here are the chart-hitting Beatles at their happiest," says the magazine. "Greece, sun, peace, quiet, and a few minutes alone with their nearest and dearest."

Role of Alex Mardas

Sarrikostas doesn’t name the “agent” who tipped him off. But several writers state that Alexis Mardas helped to facilitate publicity for the Beatles’ trip. According to Peter Brown5, Mardas even made an arrangement with a senior Greek government figure that would mean the group were not searched as they entered the country. This would have made it possible to take drugs into Greece. Mardas, says Brown, struck a deal with the official that “if the Beatles were given VIP treatment, and not searched at the airport”, the group would pose for a set of publicity pictures for the Ministry of Tourism.

This aligns with the account by Pattie Boyd (who was married to George Harrison at the time). She writes in her 2007 memoir, Wonderful Tonight, that “all I remember about the holiday is that some of us took acid, and we didn’t have to go through Passport Control because Alex’s father was so important”.

There’s no evidence that the Beatles were aware of any such purported arrangements with the Greek government, or of any plans to use them for publicity purposes – and I’m not suggesting that they were. Indeed, several accounts suggest that the group were taken by surprise by the Greek media’s attention. Alistair Taylor writes6 that “we forgave [Alexis Mardas] for leaking the news of our trip to the press without telling us”. (Via their representatives, I’ve offered Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr the chance to comment on this matter.)

Nonetheless, according to the group’s biographer Hunter Davies, attempts to use the Beatles to advance official agendas were in general not uncommon. In his authorised 1968 book The Beatles, he writes: “There has always been a certain element, very often governmental, who try to turn the Beatles’ presence or interest to their own advantage.”

This certainly seems to have been the case for the Greek colonels. Despite the regime’s penchant for arbitrary cultural bans, there was apparently sufficient concern over tourism that it was prepared to at least tolerate a visit by such supposedly disreputable musicians.

Effie G. H. Pedaliu (2016): Human Rights and International Security: The International Community and the Greek Dictators, The International History Review, DOI: 10.1080/07075332.2016.1141308

Evening News, 24 July 1967

24 July 1967

With the Beatles, 2003

The Love You Make, 1983

Yesterday, 1988