Visits by ‘British personalities’: An MP’s PR advice to the colonels

As the Beatles’ island plans took shape, a Labour politician suggested that visits by high-profile British figures could help improve Greece’s image in the UK

Most backbench Labour MPs were outraged by the colonels who had seized power in Greece in April 1967. Meanwhile, ministers in Harold Wilson’s government uncomfortably sought to accommodate the regime, despite its unpopularity with the British public. But there was one Labour politician who bucked both of these trends.

The MP for Swindon, Francis Noel-Baker, claimed that the colonels had been misunderstood. He described them as “modest, sincere men” who wanted to clean up the country’s politics. And he took various practical steps aimed at improving the regime’s image in the UK, from facilitating PR connections to reportedly helping organise a promotional event.

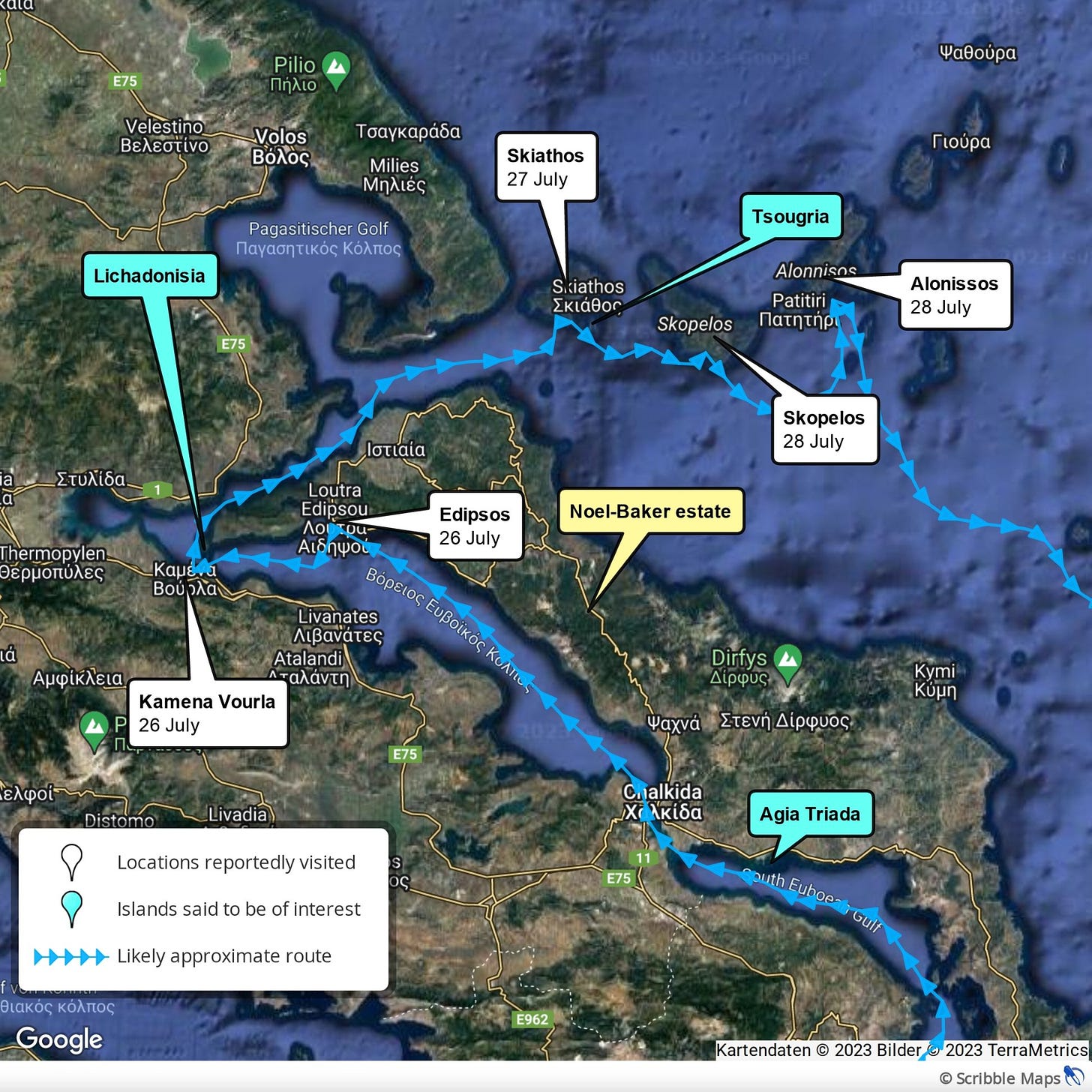

Noel-Baker also offered his own advice on publicity to the new Greek regime. This included a suggestion – about two months before the Beatles’ trip to the country – that visits to Greece from prominent “British personalities” could help improve its image abroad. This provides interesting context for the Beatles’ visit – and it also raises the intriguing question of whether there could have been a more specific connection between the MP’s activity and the group’s Greek island plans.

“…certain specific suggestions about publicity and public relations, and also about possible visits to Greece by political and other British personalities”

Interest in Greek politics

Francis Noel-Baker’s interest in Greece and its politics stemmed from his long-standing involvement with the country. His family had owned a large estate there, on the island of Evia, since 1832. (Francis ran the estate since 1956, when he inherited it together with two of his sons.) He was born in 1920 into a well-connected family. Francis’ father Philip was also a Labour MP, and could claim an array of other distinctions including a Nobel Peace Prize for his campaigning for disarmament. Meanwhile, Francis’ mother Irene Noel was “friendly with many prominent people in Greece and in England”, he wrote in his autobiography1, and “as much at home with Greek princes and with the leading Greek politicians of the day, as she was with her neighbours in the village”. He also described his mother as having been “popular at the Greek Court” in her youth.

Noel-Baker grew up in England, “in an atmosphere of international politics”2, but spent many school holidays in Greece, which helped him become fluent in the language. He cemented his own connection to the Greek Royal family in 1962 when the then Queen of Greece, Frederika, became godmother to his youngest son. And he strengthened his influence within Greek politics by founding and chairing the British-Greek Group of the Inter-Parliamentary Union, an international body. Noel-Baker, who died in 2009, wrote that through such political work he “got to know many Greek politicians and their leaders”, including “all the post-war Prime Ministers”.

Despite never holding ministerial office, Noel-Baker often commented on, and sometimes intervened in, Greek matters. This included during tensions over Cyprus in 1956, when he tried to act as an intermediary between the British government and Archbishop Makarios, the Greek Cypriot leader. This activity – which included proposing a specific four-point political solution – was described in one obituary3 as “semi-official”.

Noel-Baker took on a similarly ambiguous role in regard to the colonels’ junta, meeting leaders of the regime and other influential Greek political figures on several occasions in the months after the coup. On 8 May, for example, he had discussions in Athens with the junta’s military leaders and senior ministers – as well as a private meeting with Constantine, Greece’s 26-year-old king (who had at the time acquiesced to the coup). Later the same month the MP returned to Greece, where he had more talks with senior junta figures, as well as officials and ministers.

Noel-Baker wrote letters to the British foreign secretary, George Brown, informing him of these meetings and his thoughts arising from them. He also expressed his controversial views on the Greek regime in public. After the second trip, the MP claimed that “a large majority of Greeks is pleased by the change” of government and that it was “inaccurate” to brand the new military leaders fascists:

“On the contrary, they represent a protest against the old social and economic order as much as against Communism. They are modest, sincere men who want to clean up corruption and inefficiency and protect Greece from upheaval.”

Advice on overseas image

In the following months, Noel-Baker continued to concern himself with the junta’s image abroad. He offered advice to the regime on this topic at a meeting with its three leaders, on another visit to Athens on 14 July. Documents show that an official from the British Embassy, who met Noel-Baker after this discussion, told the Foreign Office:

“Mr Noel-Baker had taken the line with them that their public image abroad was still very bad and that moves such as the banning of Theodorakis' music and the withdrawal of Greek citizenship from persons such as Melina Mercouri...played into the hands of those who opposed the regime. The colonels had apparently queried this and Mr Noel-Baker formed the impression that they were still not very well briefed on some of the international reactions to their activities.”

Noel-Baker also took practical steps to support the junta’s public relations. According to documents in the archive of the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), he had some involvement in efforts to find a UK-based public relations company to work for the Greek government. A letter on 1 September 1967 (from an official in the London Greek Embassy’s press office to the junta’s foreign press department) gives details of four British PR companies that were being considered for a contract “to promote Greek issues” (including tourism) in the UK and possibly elsewhere in Europe. These firms – which the official had selected in response to a request on 23 June – had already carried out initial research and submitted proposals. Noel-Baker, it says, was “involved in the preliminary stage” of discussions with the companies. (The letter was copied to one of the junta’s leaders, Colonel Papadopoulos, and its general press director, Colonel Constantinos Karydas.)

In addition, a report in Private Eye magazine from July 19674 tells us that Noel-Baker had also “helped to organise” an event in June at London’s Cafe Royal where the Greek representative had made an “impassioned plea for British tourists to come to Greece”. But if we are concerned with the Beatles’ plans, the MP’s most striking intervention had come a few weeks earlier. On 6 June Noel-Baker wrote in a letter to the Greek foreign minister Paul Economou-Gouras5 that:

"I am very much distressed by the bad image Greece continues to be given by our press, and the unfortunate impressions that have gained ground in political circles here".

Noel-Baker added that he would welcome a chance to discuss this with Economou-Gouras, as well as the Greek prime minister and Papadopoulos (the junta figurehead), "and to make certain specific suggestions about publicity and public relations, and also about possible visits to Greece by political and other British personalities".

MPs’ visit to Greece

The reference to possible visits by both “political” and “other” personalities prompts the question of whether Noel-Baker had any specific people in mind. In terms of political personalities, we know that he both proposed and helped to host a visit by three British MPs to Greece in August 1967. According to archive records, Noel-Baker had suggested inviting several MPs to the country during his meeting on 14 July with the junta leaders, who “had intimated that they thought this a good idea”. On 30 August, a letter from an embassy official to the Foreign Office confirmed that such a visit had taken place, with three MPs, including the Liberal Party’s leader Jeremy Thorpe, making a trip the previous week. After spending two days in Athens, which included a cocktail party given by the ambassador and dinner with Economou-Gouras, the MPs stayed with Noel-Baker in Evia. During this time, two of the junta’s leaders as well as Economou-Gouras “arrived by helicopter and toured round the neighbourhood with the MPs” (though this did not include Thorpe, since he had “retired from the scene”).

The Beatles’ trip

What about Noel-Baker’s suggestion about visits to Greece from “other” – that is, non-political – personalities? Is there any chance he could have had the Beatles in mind here? Or could his comments have influenced the Greek government in some way relating to the group’s trip to Greece?

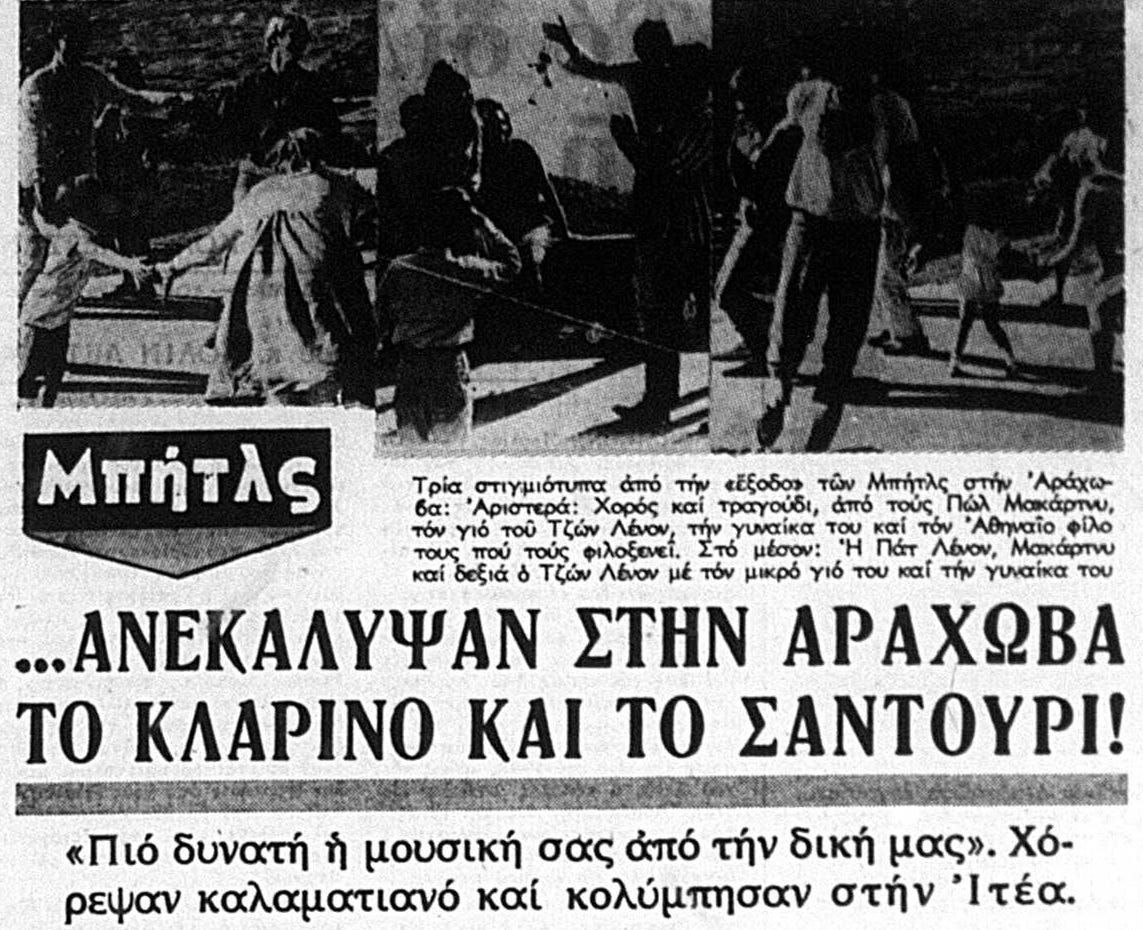

Noel-Baker’s letter aside, there is substantial evidence to suggest that Greek tourism officials were well aware of the Beatles’ trip to Greece, and helped facilitate some of the group’s activities there. According to two contemporary reports, the group interacted with at least one tourism representative on their visit to the mountain village of Arachova on 23 July. These accounts also both say that the group were offered gifts when in the village – and one of them specifies that the gifts were from tourism representatives. This article (in the newspaper Makedonia) also describes the Beatles as being “entertained by the tourism [organisation]” on that day. In addition, a number of sources allude to substantial media interest in the Beatles’ activities in Greece. And some accounts from people close to the Beatles at the time state that Alexis Mardas was involved with keeping the press or tourism authorities informed of the group’s movements.

Overlapping social circles

The involvement of tourism representatives, alongside media attendance, suggests an organised attempt to create publicity from the Beatles’ trip – and this quite possibly involved Alexis Mardas. If this impression is accurate, the question is then whether this happened independently of Francis Noel-Baker’s suggestion, or whether there may have been some kind of connection. The timing is consistent with the latter: Noel-Baker wrote his letter to Economou-Gouras on 6 June, around the same time that Mardas was discussing the possibility of the Beatles buying a Greek island.

It would have been perfectly feasible for Mardas and Noel-Baker’s paths to cross, since their social circles seem to have overlapped to some degree. The Doxiadis family was one apparent shared connection, according to records at the personal archive of Constantinos Doxiadis – the renowned architect whose daughter Alexis Mardas married in 1968. In the early 1960s the architect and Noel-Baker were among those corresponding about a proposed development project in Evia. This apparent acquaintance between the MP and Doxiadis should not be unexpected. Both men had significant social, royal and political connections in Greece, so it is very plausible that they would have been aware of each other and had shared contacts.

To what extent Alexis Mardas also had access to such networks is an interesting question. Certainly, his marriage to Euphrosyne Doxiadis in 1968 would have provided plenty of opportunities for this. It’s unclear how far this would have been the case in 1967 – although one connection in particular does seem to have existed at this time. It seems probable that both Noel-Baker and Mardas knew Sophocles Papanicolaou – the Keeper of the Privy Purse to the Greek King who since 1958 had owned Agia Triada, an island often linked to the Beatles. A member of the Papanicolaou family told me that Mardas knew Sophocles Papanicolaou socially at the time he was searching for an island for the Beatles. Given Agia Triada’s location close to Evia, and the mutual connection to the Greek royal family, it also seems very likely that Noel-Baker would have known the Papanicolaou family.

Whether or not that particular connection is relevant, the possibility highlights how Mardas and Noel-Baker apparently both had some access to the kind of social circles that included people who owned islands. And the Doxiadis family wasn’t Mardas’ only potential link to such a world. He was educated at the prestigious Moraitis School in Athens, which could have given him a range of influential connections. And if his father did work for or with the Greek state in some capacity, that could have been another source of relevant contacts.

A geographical alignment reinforces the case for a possible overlap. Newspaper reports of the Beatles’ cruise in Greece tell us that the group took a route close to the island of Evia – and the islands most plausibly linked to the group are also near Evia. This by no means proves that Noel-Baker played any role in the events. But if he did, it would not be surprising if any islands involved were close to his estate.

Intertwined

The idea of Alexis Mardas’ efforts to find the Beatles a Greek island somehow overlapping with a landowning MP’s campaigning on behalf of a military dictatorship might, on the face of it, seem surprising. And it’s of course possible that Mardas and Noel-Baker each went about their own activities oblivious to what the other was doing. But given the alignments of purpose, timing, and geography – as well as the various possible social links – it is arguably more improbable that the activity of Mardas and Noel-Baker didn’t in some way overlap. Even if there was no direct connection, Noel-Baker’s activity is still relevant to the Beatles’ plans. After all, he was advising the Greek government on the benefits of visits by prominent people, just as the Beatles were planning such a visit. And his advice may have influenced the junta, even if he didn’t know about the Beatles’ intentions.

In my opinion, the possibility of a connection is at least worth considering further. And the question highlights how the different strands of what I’m writing about in this Substack are closely linked. On the one hand, there are some very specific questions about what happened: which island the Beatles wanted to buy, where they went, how this activity came about and who was involved. These questions would all have specific answers, if it was possible to find them. But there is also the less clear-cut question of why this all happened – and this involves much wider issues to do with the political, historical, social and cultural context of the events. Noel-Baker’s activity at this time demonstrates how learning more about one strand can in turn help illuminate the others.

Francis Noel-Baker (1987) A Taste of Hardship

Francis Noel-Baker (1985) My Cyprus File

The Guardian, 1 October 2009

Private Eye, 7 July 1967

Archive of the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs