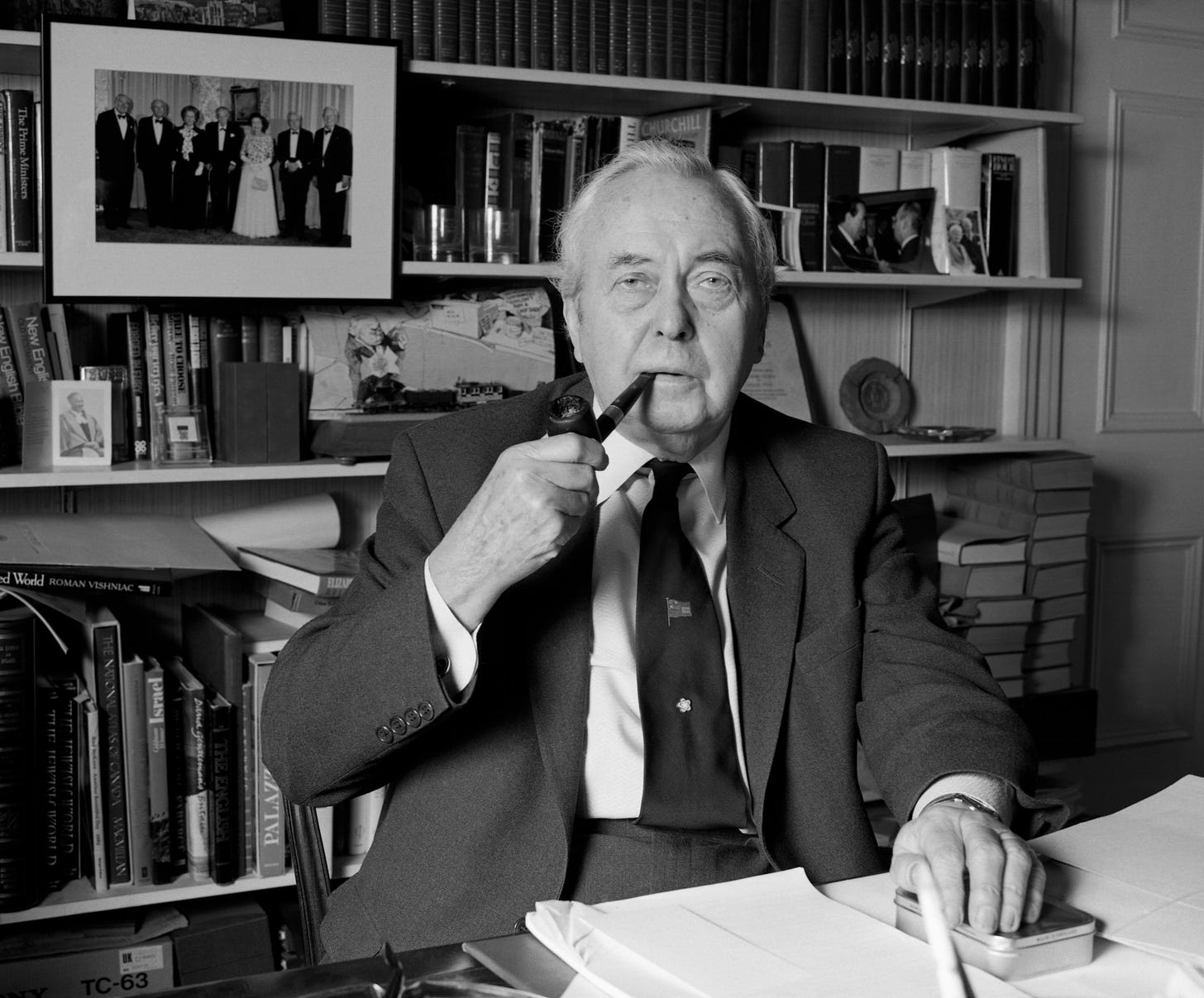

Lord Goodman: Lawyer to the Beatles - and the prime minister

The peer whose law firm worked on the group’s plans to buy an island was a confidant to Harold Wilson and a notable figure in British public life

Read more:

Where was the Greek island the Beatles wanted?

The intriguing inner circle of Alexis Mardas

From London’s summer of love to Greece’s military dictatorship

While writing about the Beatles’ plans to buy a Greek island, I’ve often found that seeking an answer to an apparently simple question – where the island was – quickly leads to a deeper exploration of the politics and society of the 1960s.

That’s certainly been the case with the letter from the Beatles’ lawyers requesting permission to obtain the currency to buy the island. The document is held in the UK’s National Archives, and includes the puzzling name for the place the group wanted: “Aegos in Konstadinos”.

The letter - required because of the rules concerning overseas investments at the time - was written by a firm of solicitors called Goodman, Derrick and Co. While that name may not ring many bells these days, it would have done in 1960s Britain. Because one of the firm’s senior partners was Lord Arnold Goodman – a man described by his biographer as “the fixer for the British establishment”.

Despite never being a minister, Lord Goodman was highly influential within British politics in the 1960s and beyond. As well as being a confidant to prime minister Harold Wilson, he chaired organisations including the Arts Council of Great Britain, the Observer newspaper’s editorial trust, and numerous other boards and public bodies. In such positions and as a talented lawyer and negotiator, he was often called on to tackle prominent problems in areas ranging from the media, to culture, and foreign affairs. His role in public life is well conveyed by the title to his own memoirs: “Tell them I’m on my way”.

“Wilson would talk to me about his problems and their supposed solutions, and seemingly consult me on the matter”

Goodman’s national profile first began to emerge in 1957, when he helped three Labour MPs win a libel case against the Spectator magazine – which had suggested they had been drunk at an International Socialist Congress in Italy. More political work soon followed, including for Labour’s then leader Hugh Gaitskell. Goodman began working for Harold Wilson when he replaced Gaitskell as leader after the latter’s death in 1963. And when Wilson became prime minister following the 1964 general election, the solicitor was soon at the “very heart” of politics - in the words of his biographer, Brian Brivati1.

In his memoirs, Goodman recalls being “a frequent visitor to Downing Street”, attending once or twice a week “throughout the whole of Harold Wilson’s first premiership”, which lasted from 1964 until 1970.

“These meetings were largely an opportunity for Harold Wilson to use me as the wall of a fives court against which he banged the ball,” recalled Goodman. “Sitting in the Cabinet room at Downing Street, with the Prime Minister taking me into his confidence was an exhilarating experience from first to last.”

Goodman found the late evening discussions, which often lasted for hours “until midnight or past”, “immensely interesting because Wilson would talk to me about his problems and their supposed solutions, and seemingly consult me on the matter”.

Goodman writes that through his “politico-legal activities”, he “rapidly acquired the confidence of the leadership of the Labour Party”, adding: “Through my office door there flowed an increasing number of Labour politicians seeking professional and personal advice on a score of topics.”

Powers of persuasion

His access to Wilson made Goodman, according to an obituary in The Independent by the publisher Anthony Blond, “more influential than any cabinet minister”. He was made a peer in 1965 and in the subsequent years became “the totem and oracle for the great and the good”, with roles overseeing an array of quangos and public bodies. When in 1976 Goodman became Master of University College, Oxford, “he held 19 chairmanships of public significance and many more private, from race tracks to childhood trusts”, writes Blond.

One of Goodman’s most significant roles was chair of the Arts Council of Great Britain, which he was appointed to in 1965. In the ten following years, his “presence was also felt” at various other arts organisations, as well as the Housing Corporation, the British Council, the Observer Trust, and “numerous committees of inquiry”, writes Brivati2.

Goodman’s keen intellect is well-attested, but his personal qualities were equally crucial to his influence. Blond describes him as “the greatest negotiator of the age”, while Brivati3 writes that Goodman “had charm, he was witty, and he could frequently persuade people to do what he or his clients wanted”.

He also had a tougher side, according to Brivati, who writes that Goodman proved useful to many through his “power to intimidate journalists”. One example of this was in 1964, when Goodman helped gain an apology from the Daily Mirror and a settlement of £40,000 for the Conservative peer Lord Boothby over scandalous media reports involving connections to the criminal underworld – despite there being photographic evidence. Goodman’s intervention, says his biographer, indicates how “proprietors would do deals over the heads of editors when Goodman was involved”4.

Connection to the Beatles’ island plans

Goodman’s range of distinguished clients included the Beatles. In his memoirs, he recalls advising Lennon and McCartney on the 1965 flotation of Northern Songs. And “some years later”, Goodman writes, he “became involved in sorting out various tax affairs on the Beatles’ behalf”, and “was also asked to advise them in relation to possible investments”. The latter included a machine which could transcribe songs into musical notation – which Goodman recalls “very strongly” urging the group against.

It isn’t clear whether Goodman had any direct involvement in the planned island purchase. His law firm wrote the letter to the Bank of England on the Beatles’ behalf, applying for permission to buy currency to purchase an island. But the document is simply signed in the firm’s name of “Goodman Derrick” rather than by a named individual (and we know that other lawyers at the practice also worked on matters to do with the Beatles). So, it’s not clear whether Goodman had any personal involvement in this particular issue. But given his work on other aspects of the Beatles’ affairs, it seems likely to me that Goodman would at least have known about the group’s island plans and his firm’s role in them.

If this was the case, then Lord Goodman is one more politically significant figure in Britain with knowledge of the Beatles’ Greece plans as they were progressing. (The others include a very senior civil servant as well as a senior government minister.)

In July 1967, policy towards Greece presented a high-profile dilemma for Harold Wilson’s government, which was being pulled in different directions by moral outrage at the Greek junta and the pragmatic demands of cold war geopolitics. The issue was discussed at cabinet and by civil servants. And it seems plausible, if not likely, that it may have come up in the prime minister’s long, late evening chats with Goodman. (Even if it didn’t, Lord Goodman took an interest both in foreign affairs and the media, so would presumably have been aware of the Greece situation.)

Today, we are familiar with the idea that what celebrities say and do can have an influence on politics. In the sixties, the power of celebrity wasn’t yet so deeply ingrained in society. But the Beatles’ Greek island plans did have the potential to have an influence on UK public opinion about Greece, and therefore on British politics. As I wrote previously, if faced with a similar situation today, it seems likely that a British government would consider the ‘optics’ of whatever decision it made.

It’s difficult to assess to what extent the people in British politics who were aware of the Beatles’ island plans at the time may have considered the political dimensions of them. The involvement of Arnold Goodman’s law firm adds a further complication to that question.

Read more:

Where was the Greek island the Beatles wanted?

The intriguing inner circle of Alexis Mardas

From London’s summer of love to Greece’s military dictatorship

ODNB

Brian Brivati (1999) Lord Goodman

ODNB

Brivati (1999)