John Lennon’s island fantasies

Considering Lennon’s interest in islands could help us understand his idealism, his reading habits, and his musical and literary writing – perhaps even his relationship with his father.

While there may be some confusion about which Greek island the Beatles wanted to buy in 1967, there’s little doubt that most enthusiastic of the group about buying one was John Lennon. And from writing about these events, I’ve realised that Lennon’s interest in islands went way beyond this. He seems to have been fascinated by them. And I think examining that fascination might tell us quite a lot about John, and how his personal relationship to islands forms part of wider cultural patterns.

Exploring Lennon’s interest in islands, for example, might help us understand how he thought and felt – including his utopian and idealistic tendencies. It could give us some clues about his reading habits. It might give us a new way of looking at the Beatles song, Dr Robert. It can help shed light on his apparently nonsensical literary writing. And I think ultimately, it can help us understand Lennon’s relationship with his father.

Read more:

The intriguing inner circle of Alexis Mardas

George Harrison on Monolia?

However unrealistic Alfred’s plan was, in John’s young mind that decisive parting with his father may have been associated with the idea of moving to an island.

Idealised lifestyles

These themes become clearer when we look at the various ways Lennon’s interest in islands manifested. It was of course the mysterious figure of ‘Magic’ Alexis Mardas – the electronics whizz introduced to the group as John’s “new guru” – who persuaded the Beatles to visit Greece in search of an island. But the idea of them living communally seems to have been under discussion already. And we can see from the comments made by John that he in particular was considering the possibility in some detail. This is what he said to a journalist while the group were in Greece:

“…we are seriously thinking of buying a small Greek island and setting up our own hippie commune there, so we can do what we want without anyone disturbing us. We’ll build villas there for us and our colleagues and live there six months of the year.”1

The Beatles biographer Hunter Davies tells us that John was “particularly keen on” the Greek island idea, saying it was “discussed for many weeks”. Davies adds that “it even got to the stage of what to do about Julian and his schooling” – referring to John’s son, who was four years old at the time.

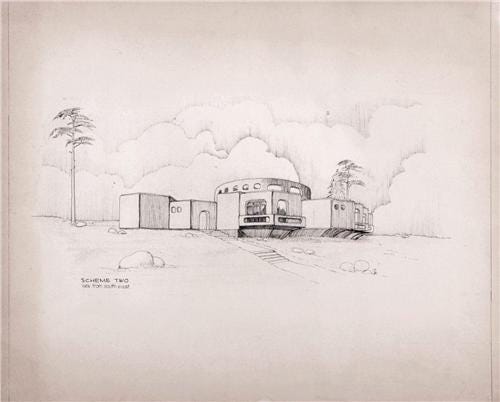

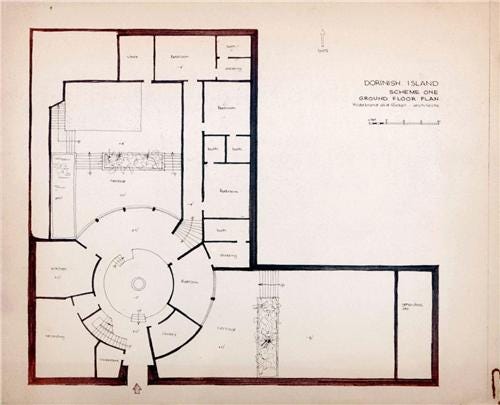

A few months before the Beatles went to Greece, John had already bought his own island, in the country of Ireland. The island was called Dorinish – one of many islands in Clew Bay, County Mayo. Lennon bought it in March 1967. He only visited twice, but he had plans to build a house there. And in 1970, John imagined a future when he and Yoko Ono were “a nice old couple living off the coast of Ireland”. A community of hippies lived on Dornish in the early seventies, who Lennon donated money to. But in the end, Yoko sold the island a few years after John died.

But the fact that Lennon bought Dorinish, and then a few months later was encouraging the Beatles to buy another island, does underline his fascination. And I think we can connect this fascination to Lennon’s tendency towards idealistic and utopian thinking. We see that tendency in Lennon’s political activism. We also see it in his songs – from the optimistic yearnings of Imagine, to the dream-like nostalgia of Strawberry Fields Forever. And we can also see it in the imagined island lifestyles in Greece and Ireland that John fantasised about.

It's interesting to look more closely at the connections between islands and fantasies – both in terms of John Lennon’s specific experiences, and in a wider cultural sense. Because islands are physically isolated, they’re often places where society’s norms can be suspended or upended, and where different ways of living can be explored. Indeed, the word utopia – which means nowhere – was coined in 1516 as the name of an imaginary island. It’s the title of a book by Thomas More which describes an idealised civilisation on that island. Unlike the Tudor England More lived in, in his utopia there’s no money or private property, there’s freedom of religion, and war is despised.

So for both More and Lennon, islands offered the chance to imagine societies completely different to their daily realities. And this role of islands continues to the modern day. In a book published in 2020 called Island Dreams, the writer Gavin Francis explores his own fascination with islands. On his travels, Francis comes to this realisation:

“There seemed to be a connection between a certain kind of sparsely populated island, remote from urban centres, and dreams. Or perhaps it is that such islands have the power of concentrating dreamers.”

Aldous Huxley: John’s ‘new guvnor’

As well as being a dreamer, John Lennon was also a big reader. And I think it’s possible that a particular book may have played a part in his interest in islands. That book is called Island. It was written by Aldous Huxley and published in 1962. Huxley was a big influence on the 1960s counterculture because of his writing on psychedelic drugs, particularly his account of taking mescalin in his book, The Doors of Perception.

Huxley features on the Sgt. Pepper album cover. And John Lennon in particular had a strong interest in him. In 1966, he included “Aldous Huxley books” among the “prized possessions” he listed to the journalist Ray Coleman. John explained: “I’ve just started reading him because he’s the new guvnor, it seems to me”. I’ve not seen any specific evidence that John read Island. But we know he liked Huxley, and we know he liked islands. So I think it’s worth looking at that book’s content and how it might relate to Lennon’s life and work.

Huxley’s Island: Palan society and Dr Robert

Huxley’s Island centres around a civilisation on the remote Pacific island of Pala. People live there in peace, plenty and good health, combining Eastern philosophy with Western science. The insights gained through a hallucinogenic fungus called the moksha-medicine help create a utopian society. On Pala, there’s no military and little crime. There’s economic equality, political autonomy, and no established church. So there’s plenty of common ground with Thomas More’s utopia – and more than a passing resemblance to the lyrics of Lennon’s Imagine.

At the start of the book, a cynical British journalist called Will Farnaby is shipwrecked on the island. A doctor called Robert McPhail – who’s descended from one of the society’s founders – helps Farnaby recover. Through his conversations with this doctor and other people, Farnaby gradually comes to understand and embrace the Palan way of life. The book culminates with Farnaby sampling the moksha-medicine and glimpsing enlightenment.

When I read Island, what strikes me is that not only is Dr Robert McPhail a central character in the book – but that he’s consistently, and frequently, referred to by the specific name, “Dr Robert”. So, could (as some have suggested) the book have inspired Lennon when writing the Beatles song with that name? The song is typically seen as a sort of sly joke, referencing either a specific New York doctor, called Robert Freymann, or the art dealer Robert Fraser. Both of those people were known for providing drugs. But I think we can also read the song more earnestly, as a Huxleyan story of enlightenment through psychedelics. After all, in the song, Dr Robert has a “special cup”. He “helps you understand”, “see yourself”, and indeed become a “new and better man”.2

I think those themes correspond closely to the personal journey of Will Farnaby in Island. He moves from an attitude of scepticism and exploitation towards understanding and insight. And some of the song’s language recalls Huxley’s Island. The word ‘understanding’, for example, is used repeatedly in the final section of the book, when Farnaby takes the moksha-medicine. Here’s a quote from that passage:

“It was not only bliss, it was also understanding. Understanding of everything, but without knowledge of anything”.

Gurus and father figures

Lennon was interested in Huxley, he was interested in islands – and he loved word play and double meanings. So I think the idea that the book’s character of ‘Dr Robert’ was one inspiration for the song is certainly plausible. But just as interesting is the way that the book’s story fits into wider cultural patterns.

Huxley’s Island isn’t a straightforwardly positive narrative. At the end of the book, it’s clear that the paradise of Pala will not last much longer, and Dr Robert himself is executed. That transience aligns with many other island stories, which play with the idea that the location is not entirely real. But even when they are fantasies, islands still offer real value. As Will Farnaby’s story shows, their strangeness can present new challenges that bring about personal struggles and crises. And this can lead to growth and change if the characters respond appropriately.

This tendency is linked to a literary trope that we can see in the figure of Dr Robert. Where an island represents the disruption of established norms, there’s often an intermediary character. And this person, who is typically male, acts as a bridge between the familiar world and the world of the island. They may be represented as wise and admirable, but also subversive and potentially dangerous.

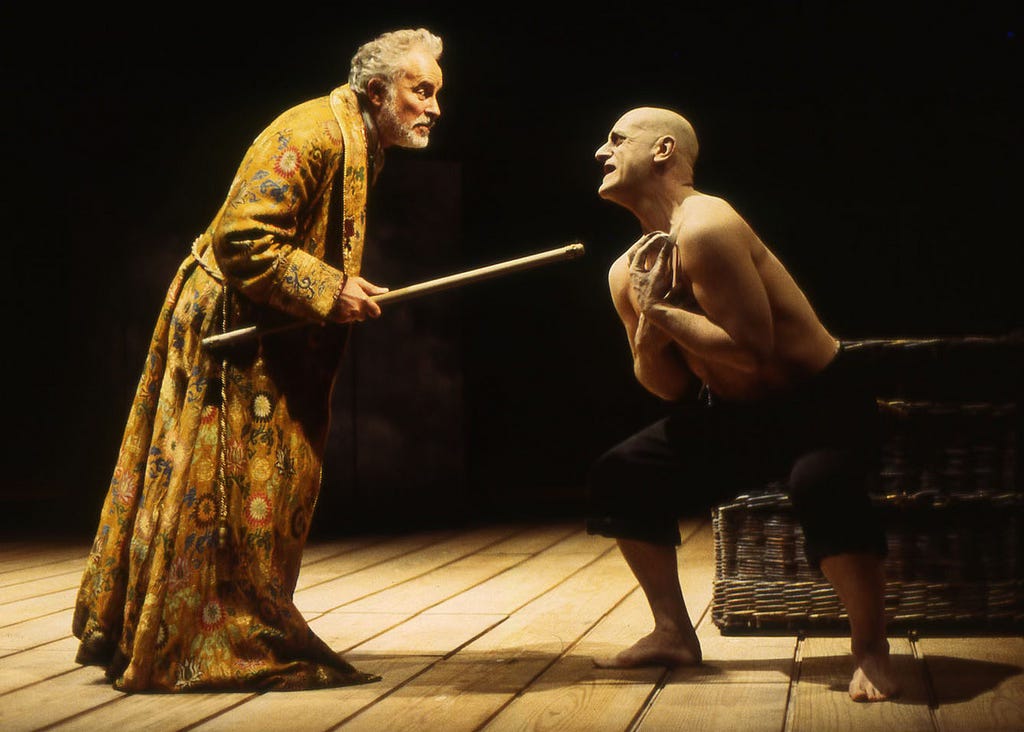

In More’s Utopia, the account of the island society is related by a mysterious traveller called Raphael Hythloday. Hythloday is praised for his eloquence and knowledge, but also presented as an unkempt outsider – “sunburnt, with a shaggy beard and a coat slung carelessly over his shoulder”. Another island-based story is Shakespeare’s Tempest. In that play, the central character is the deposed duke of Milan, Prospero, who has been exiled to a remote island. Prospero learns magic on the island, which he uses to bring about a shipwreck and then control the people who are stranded. Some of those people previously betrayed Prospero. But at the end, the play allows for hope, forgiveness and some reconciliation.

For me, Raphael Hythloday, Robert McPhail, and Prospero are all examples of these ambiguous intermediary figures, who use their island-gleaned knowledge to guide others towards insights and awareness. Indeed, we could describe them as gurus. And gurus are something that John Lennon had an abiding interest in. He consistently developed significant relationships with male mentors and role models. Some early examples of these are the Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein, and George Martin, their producer. In the mid-sixties Lennon met Alexis Mardas, who he introduced to the group literally as his “new guru”. Soon afterwards he visited the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi to learn meditation in India, and later saw the primal therapist Arthur Janov. All of these men gained John’s admiration and sought to influence him through new experiences, understanding or even enlightenment.

Alfred Lennon: ‘married to the sea’

So what drove Lennon’s gravitation towards these figures? I think it probably had something to do with his father, Alfred Lennon. John saw very little of his dad throughout his life. Alfred’s work as a merchant seaman meant from John’s birth until he was three, his father had only spent about three months in Liverpool. We’re told that John’s mother Julia complained that Alfred was “married to the sea”. Following numerous disruptions and marital discord, from the age of five John’s main carer was his maternal aunt, Mimi Smith. He didn’t see Alfred again until he was 23. And in 1980 Yoko Ono highlighted this lack in John’s life, saying: “I think he has this father complex and he’s always searching for a daddy”.

We’ve seen how from a cultural viewpoint, islands are often associated with these guru-type figures. And I think it’s interesting how this dovetails with the specific circumstances of Lennon’s life. There’s a clear connection between his father’s absences and the sea, and John seems to have been deeply aware of this. In a memoir by Pauline Lennon – who was Alfred’s second wife – she describes John’s “love/hate relationship with the sea”, writing:

“Since early childhood the ocean had held a romantic fascination for John as the means whereby Freddie had escaped from Liverpool to live a life of freedom and adventure and John in turn had yearned to follow his father’s example and himself run away to sea.

But at the same time John had long harboured feelings of fear and resentment towards the sea for having stolen his father from him…”.

Some of Alfred Lennon’s absences have a connection with islands specifically. He made trips to the Mediterranean and the Caribbean. And in 1943, he was detained on Ellis Island in New York after deliberately missing his ship.

And the possibility of John moving with his father to live in the island nation of New Zealand is at the heart of a notorious incident in Blackpool in 1946. In the traditional version of that story (which Alf Lennon told to Hunter Davies) the five-year-old Lennon was forced to choose between his father and his mother. John was all set to emigrate to New Zealand with Alfred, before at the last minute running to stay in Liverpool with Julia. The renowned Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn offers us a less dramatic version of this story3 - but here, too, the possibility of John living in New Zealand comes up in the discussions. Whatever actually happened, it must have been bewildering for John. And however unrealistic Alfred’s plan was, in John’s young mind that decisive parting with his father may have been associated with the idea of moving to an island.

Lennon’s own reading and writing

So I think there are some fascinating parallels between John’s interest in islands, his interest in gurus, and his father’s absences. Those absences were linked to the sea, and sometimes specifically to islands. The figure of the electronics ‘wizard’ Magic Alex, who guided the Beatles around Greek islands in 1967, brings together John’s interest both in islands and in gurus particularly clearly. And we might also see the discussions that year about moving Lennon’s four-year-old son to an island as an echo of John’s experience in Blackpool decades earlier.

And while we don’t know whether Lennon read Huxley’s Island, he had a clear interest in another island-based story – Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson. Lennon named this as one of the children’s books that had “opened up [his] whole being”. The book and its characters – like the charismatic pirate Long John Silver – were well known in post-war British culture, partly through film and TV adaptations. And the character of Long John Silver is said to have inspired one of the Beatles’ early names – Long John and the Silver Beetles.

An important theme in Treasure Island is the father-son dynamic. The narrator is a teenage boy called Jim Hawkins, whose father dies early in the book. And the relationship Jim forms with Long John Silver – despite the pirate’s moral ambiguity – helps Jim see new perspectives and mature.

John Lennon highlights this aspect of the story in his own literary work. In 1964, he published a collection of writing called In His Own Write – which has seen him compared to writers like Lewis Carrol and even James Joyce for the book’s word-play and surrealism – and it contains many of Lennon’s own illustrations. One of the stories is a parody of Treasure Island called Treasure Ivan, featuring the characters Large John Saliver and Small Jack Hawkins. In that story, Lennon writes:

“Large John began to look upon Jack as a son or something, for he was ever putting his arm about him and saying ‘Ha Haaaaar’, especially with a Parable on his shouldy.”

The next year, Lennon published another literary collection called A Spaniard in the Works, which also includes an island-based story. A 30-stanza poem called The Wumberlog (Or the Magic Dog) tells the story of a boy who escapes from his home to travel to “the land / Where all the secrets hid”. Guided by a friendly magic dog and a bird called a wumberlog, he rows a boat to an island where “wondrous peoble” [people] … “live when they are dead”.

When the boy gets to the island, he finds the people digging holes and burying each other up to the neck. Personally, I think we can see the boy’s journey to the island of secrets in this poem as a way of Lennon exploring the secrets in his own psyche. We can see this particularly in the penultimate two stanzas – which are talking about the people on the island:

Without a word, and spades on high,

They all dug deep and low,

And placed the boy into a hole,

Next to his Uncle Joe.

‘I told you not to come out here,’

His uncle said, all sad.

‘I had to Uncle,’ said the boy.

You’re all the friend I had.’

To me, those verses convey the loneliness of Lennon’s childhood, when he did actually have to go and live with his uncle (and aunt). They were, in other words, “all the friend [he] had”. John developed a particularly warm relationship with his uncle George Smith (Mimi’s husband), who was indeed a substitute father figure. George died when Lennon was fourteen. And the journey to the strange island in this poem could be a way of Lennon addressing that loss.

The poem also highlights how the association between islands, and guru or father figures, is a recurrent theme. Not just in culture generally, but also in John Lennon’s literary writing and in his actual life. When I first noticed this, I found it quite surprising. I wasn’t expecting the same theme to come up so often in different situations. But when you think about it, islands provide opportunities for introspection, as well as growth and change. So perhaps it isn’t quite so surprising that they often prompt people to grapple with their most fundamental relationships.

Bermuda

These themes really come into focus in the last year of John’s life. As the culmination of a growing interest in sailing, in summer 1980 Lennon took part in a 600-mile yacht trip to Bermuda. On the way, the boat was caught in a violent three-day storm, and for six hours John unexpectedly had to take the helm himself. Being thrown into this situation proved to be a profound and cathartic experience which Lennon described as “the time of [his] life”. The boat’s captain felt that the drama “connected [John] in some way with his dad” and “brought some huge healing”.

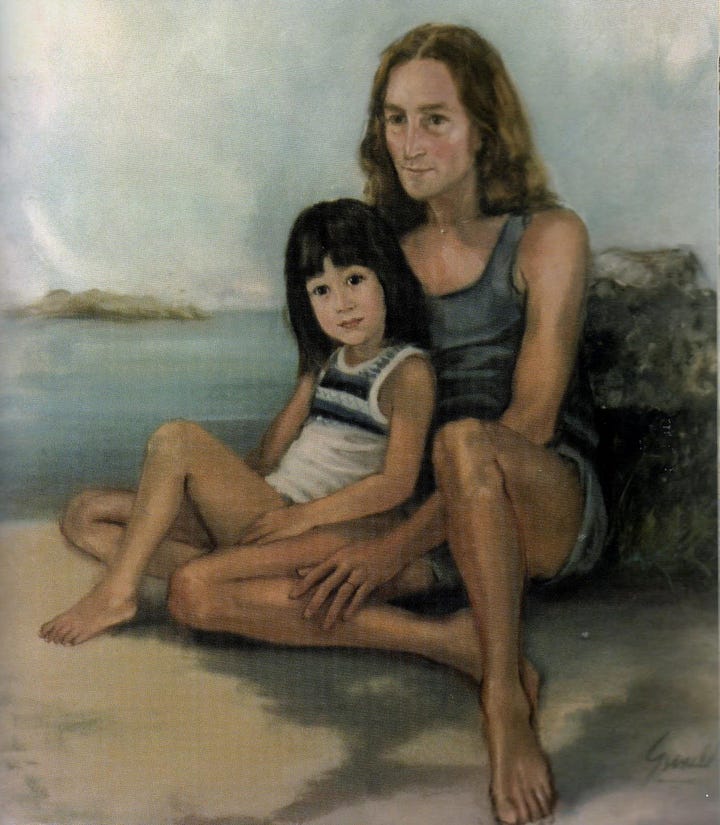

Until then, John had been living a domestic life for years. But he later said that after this voyage, he felt “tuned in, or whatever, to the cosmos. And all these songs came!” During two months on Bermuda, Lennon experienced a creative resurgence. He worked on many songs for he and Yoko’s album Double Fantasy – named after a flower that John saw on the island. John was joined on Bermuda by his younger son, Sean, who was then almost five. Together, they had their portrait painted by an artist who noted the pair’s “beautiful relationship”. The painting was later hung above a piano in John’s Dakota apartment in New York.

So as I’ve discussed here, islands in culture are not only connected with fantasies. They’re also often locations for existential struggles, the exploration of father-son relationships and personal growth. And in Lennon’s last trip to an island, he seems to have convincingly faced up to these challenges himself. The touching images of him and Sean on Bermuda suggest he had moved beyond his troubled relationship with Alfred to develop a warm connection to his own son. These feelings are clearly expressed in Lennon’s song, Beautiful Boy – which he recorded a demo for on Bermuda – and which begins and ends with the sounds of the ocean.

Months after his trip to Bermuda, John’s life would tragically end. But on that most remote of islands, his lifelong fascination had eventually led him to real rewards: peace, fulfilment and creative renewal.

This post is based on a presentation I gave at the International Beatles Symposium at Liverpool Hope University in July 2024.

Labis Tsirigotakis, Αναμνήσεις Ζοής (2023)

In Beatles '66 (2016), Steve Turner discusses the apparent references of the song’s lyrics to psychedelic drugs

Mark Lewisohn, Tune In (2013)

I recall that around 1964 or ’65, Donovan appeared on a NYC TV pop music show wearing a shirt on which he had drawn a map of an island. After performing, the host asked him about the island, and when Donovan began an explanation, the host, pressed for time, quickly thanked him for coming on the show and went to a commercial break. But in the few seconds that Don had to discuss the shirt, he began to go into what seemed like a very detailed philosophy – so much that I remember that little incident to this day.

I mention this, because years later, an official fan club for Donovan was started, and that was called “Donovan’s Isle.” Given his close association with The Beatles, I always wondered if he had some influence over them regarding the Greek island issue.

Outstanding analysis! I thoroughly enjoyed this and would love to have seen your presentation at the Liverpool Symposium. Was it recorded?