'Alex said they could pay less tax in Greece’: the financial context of the Beatles’ island plans

Alexis Mardas is said to have claimed that he could help the Beatles ‘pay a lot less tax in Greece than they were paying in England’

Read more:

Lord Goodman: Lawyer to the Beatles - and the prime minister

Actor, architect, soldier…spy? The intriguing inner circle of Alexis Mardas

Where was the Greek island the Beatles wanted? The evidence

The Beatles’ plans to buy a Greek island sometimes seem like a romantic vision, epitomising the idealistic aspirations of the 1960s. And this impression is supported by comments from members of the group that they wanted a “sort of hippie commune” (Paul McCartney) where they could “drop out” (George Harrison).

I don’t doubt that these motivations existed - but the plans also had pragmatic aspects. I’ve already written about the political dimensions. And naturally, there would also have been financial considerations for such a significant proposed purchase. As far as I know, none of the Beatles have commented directly on this aspect of the plans. But for some of those involved, including the group’s then financial adviser Stephen Maltz, the island plans were apparently seen as a possible way of reducing the amount of tax that the group paid.

‘Major tax problem’

At the time, the UK’s tax structures led to much higher rates for the highest earners than is now the case. In summer 1967, the basic income tax rate was 41%, with an additional “surtax” of up to 50% charged on the proportion of income above certain thresholds. This led to the highest earners’ income being taxed at rates of up to about 90 per cent. And of course, depending on individual situations there were various other taxes to consider too.

The Beatles’ commercial success therefore meant they were potentially liable for very large amounts of tax. In his book Many Years from Now, Paul McCartney’s biographer Barry Miles confirms that by 1964, the “staggering amounts of money” that the group earned meant that the Beatles now “found themselves with a major tax problem” - with John and Paul, as songwriters, earning more than the others.

Capital was taxed at lower rates than income, and therefore a key consideration for the people advising on the group’s finances was to explore ways to convert income into capital. Miles explains how this idea motivated the advice to float Northern Songs (the company that handled Lennon and McCartney’s songwriting royalties) on the stock market in February 1965. The flotation meant John and Paul "would not pay any tax on the proceeds when they sold their shares on the exchange,” writes Miles. (At the time, there was no capital gains tax - and although this was introduced later in 1965, it was still at a lower rate than income tax).

The flotation proposal was made by James Isherwood, then a partner at the accountancy firm Bryce Hanmer Isherwood (later Bryce Hanmer after Isherwood left in 1965), which advised on the Beatles’ finances for much of the 1960s. In 2015 I met another former partner at the firm - Harry Pinsker, who worked extensively on the group’s financial affairs. Pinsker, who died in 2021, explained to me: “The Beatles became successful. One always was looking for ways and means of turning income into capital to save them paying tax.”

Alexis Mardas “said he had very good connections in Greece and could help the boys resettle and pay a lot less tax in Greece than they were paying in England,” writes Stephen Maltz.

The Beatles’ financial ‘mess’ and Apple Corps

In 1965 Stephen Maltz, who had recently joined Bryce Hanmer Isherwood as a newly qualified accountant, was tasked by Pinsker with “looking after” the Beatles’ financial affairs, he recalls in his 2015 book, The Beatles, Apple and Me. He soon realised that due to a lack of records of the group’s earning and spending, he would have to start “virtually from scratch”. After several months of work, he concluded that the Beatles’ finances “were in a mess”.

At a meeting in April 1966, Maltz informed the Beatles of the “financial reality” they faced. Until he had begun work on their finances, Maltz writes, no accounts had been prepared for the group since their company, The Beatles Ltd, was set up in 1963. He recalls telling the four Beatles:

"Gentlemen, I've been studying your financial affairs, and the reality is that two of you are close to being bankrupt and the other two could soon be, as well. You have earned a lot but you have also spent a lot and no money has been put aside for taxes. You owe the taxman hundreds of thousands of pounds.”

Following this, Maltz had the impression that his comments produced “four angry and bemused Beatles”. That certainly appears to have been the case for George Harrison, who (apparently referring to the time around April 1966 when the band were recording their album Revolver) in The Beatles Anthology book, is quoted on the amount of tax paid by the group:

“In those days we paid nineteen shillings and sixpence out of every pound (there were twenty shillings in the pound) and with supertax and surtax and tax-tax it was ridiculous – a heavy penalty to pay for making money.”

This was around the time when Harrison wrote the song Taxman, with its sardonic lyrics such as: “Should five per cent appear too small / Be thankful I don’t take it all”. Ringo Starr is quoted in the Anthology book saying “we were pissed off with the tax situation” - though it’s not made clear exactly what time period this refers to.

The Beatles’ financial and legal advisers had the task of remedying this situation. The strategy that was developed, writes Maltz, included working (with eventual success) to negotiate a refund for a large amount of tax deducted from the Beatles’ earnings in the US. He says he also urged the group to be more careful about their personal spending. In addition, Pinsker and Maltz (who became a partner at Bryce Hanmer following Isherwood’s departure) advised on developing a new business structure for the group - discussions that would eventually lead to the creation of the Beatles’ multifaceted company, Apple Corps.

In his book, Maltz writes that Bryce Hanmer, through “lengthy discussions” with lawyers, developed the idea that the Beatles could, in effect, buy shares in themselves. At the time, the Beatles operated through their company, The Beatles Ltd. But the new approach conceived of the group as a partnership, known as ‘The Beatles and Co’. In April 1967, 80% of The Beatles and Co was sold to The Beatles Ltd - which was soon afterwards renamed as Apple Music, then Apple Corps.

Maltz writes that with this structure, while the Beatles would need to pay capital gains tax, this would amount to “a lot less” than the income tax and corporation tax that they and their company would have owed under the previous arrangement.

Another strand of the plans that Maltz was working on was to diversify the group’s business activities. The thinking was that developing their existing film and music companies, and branching out into other areas, could “produce income when [the group’s] musical and acting careers ended”, Maltz writes. A further benefit would be that some funds could be used to “buy property and provide a solid asset base”, Maltz says in his book. He explains that demonstrating this kind of capital investment would “make it difficult for the [Inland] Revenue to tax the Boys individually.”

As Apple Corps grew over the subsequent years, music was always an important focus of the business - both as a publisher and record label. Through various divisions and subsidiaries, the company also made sometimes short-lived forays into various other fields including retail, film, and electronics – the last through a company headed by Alexis Mardas. Maltz left Bryce Hanmer to work for Apple directly in January 1968 as business and financial manager, and he writes that the company had about 60 employees by the end of June that year.

The events that led to the formation of Apple are apparently referenced in a succinct quote from John Lennon included in the book, The Beatles Anthology. In 1968, Lennon said on US TV (The Tonight Show): "Our accountant came up and said, ‘We've got this amount of money. Do you want to give it to the government, or do something with it? So we decided to play businessmen for a bit.”

3 Savile Row, the location of Apple Corps’ headquarters from July 1968. Poirier2000, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

‘Resettle and pay a lot less tax in Greece’

Apple experienced various problems in its early years, and Maltz stepped down from his role there in October 1968, concerned at the “mess” he believed the company was then in. But at the time the Beatles were making plans to buy an island, he was still helping to plan the restructuring of the group’s business affairs. And according to Maltz, in June 1967 Alexis Mardas suggested to him that buying a Greek island could itself be a way of saving tax.

In his book, Maltz says that Mardas had been talking to the Beatles about them “buying a Greek island and leaving England with their families to lead a less stressful life”. John Lennon, he adds, wanted Maltz and Mardas to meet to discuss “how [the Beatles] could buy an island and whether it would be good for their tax situation”.

Maltz also recalls in his book that the subject of the island came up when he met Mardas on 16 June 1967 to discuss the possibility of the latter working for Apple. Mardas told him then, Maltz writes, that he understood from John Lennon and George Harrison that they were not happy with the amount of tax they were paying.

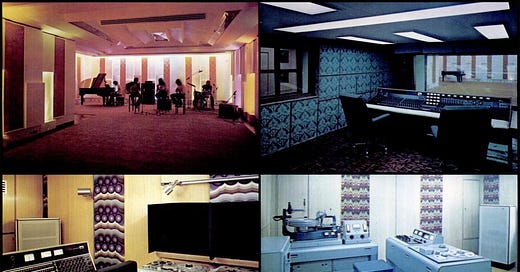

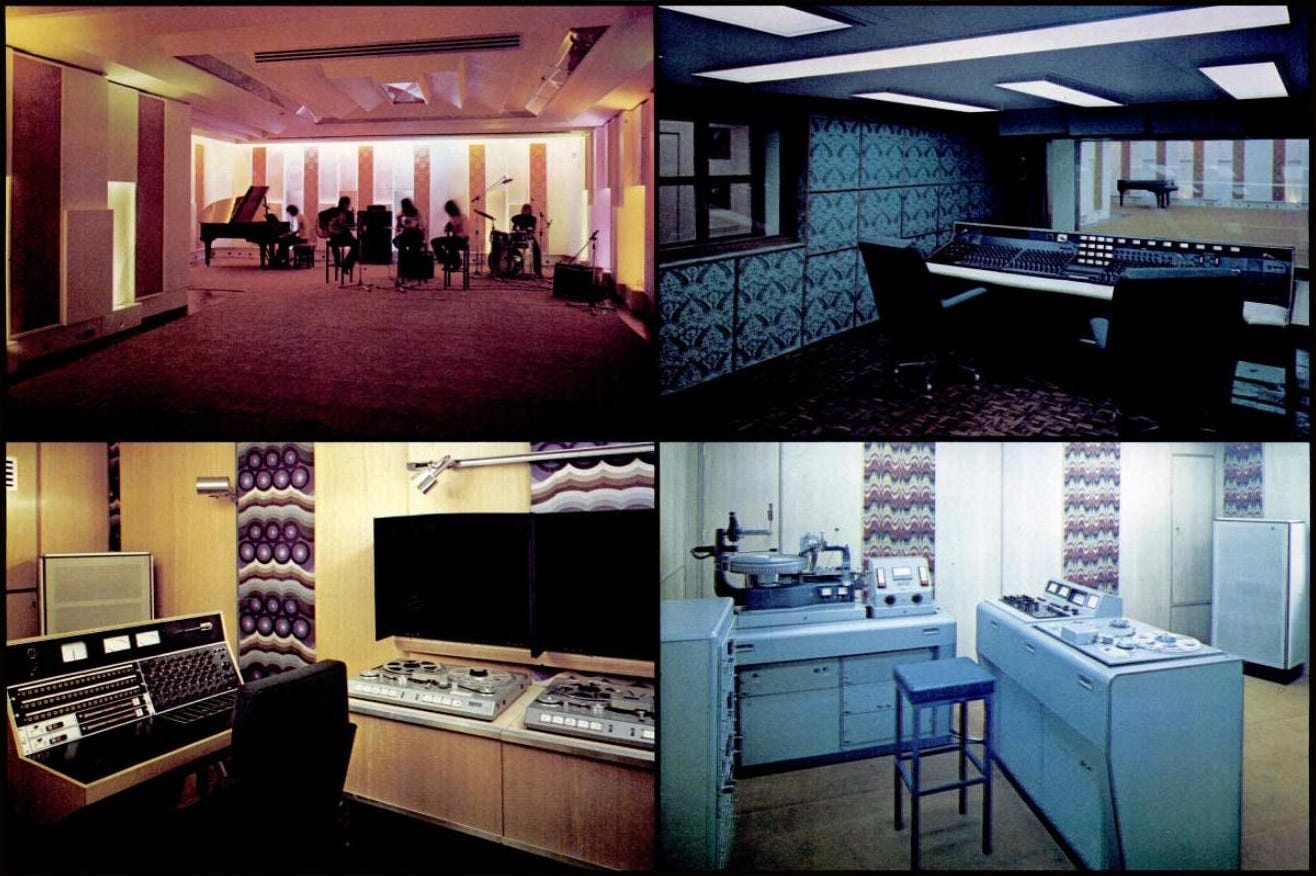

Mardas “said he had very good connections in Greece and could help the boys resettle and pay a lot less tax in Greece than they were paying in England,” Maltz adds. Maltz “immediately saw the financial possibilities”, he writes, but doubted whether the Beatles would want to leave England. Mardas, though, informed him that “he had already talked to them and they were interested to find an island on which all of them could live and that Alex could build them a recording studio so they could continue to work on their records”.

In 2017, I spoke to Stephen Maltz by phone about the Beatles’ island plans. Explaining how Mardas told him about the idea, he said: “Alex came and said that if they [The Beatles] all left the UK and went to Greece, he could help try and get a more favourable tax charge for them.”

Regarding the proposed island plans, Maltz told me:

"It was just a place that they could go and live, [with] enough housing for them. And the idea was to build a recording studio there where they'd do all their music. Go in whenever they wanted and record something. And then presumably send whatever they recorded on tape back to England. And they'd save on their taxes. That was the general idea.”

Maltz told me that he and Mardas had visited Athens in summer 1967, when they had met lawyers to explore the feasibility of the plans. "It was exploratory," he said. "Alex had said this was an island for sale. Fine. It was just to check whether it could be bought or not and the mechanics of doing it. And that they would also be able to leave Britain and save on their taxes. And they'd all live together and there was going to be a recording studio there and everything.”

He added: "I went to the lawyer to find out what the regulations were in order to buy property and register it, how to do it, setting up a company to do it, individuals buying – it was a very, very general thing.”

When I asked Maltz how serious, in his impression, the island idea was, he said: “It was a thought. I mean, it may have worked out. I don't know – but everything stopped once Brian [Epstein] died [on 27 August 1967]…They may have been serious at the time, and then dropped it.”

From what Maltz told me, and the account in his book, it seems that in his understanding the possibility of the Beatles saving tax was connected to the idea that the group might “resettle” or “go and live” in Greece. But the details of how this might have worked weren’t specified in either instance. When in September I contacted Maltz again, seeking to clarify the details of how the island plans might have helped the Beatles save tax, he referred me to the information he provides in his book.

‘Six months a year’

How did the Beatles themselves see the island plans? They may of course not have thought about them in the same way that Maltz did. And Mardas may not have presented the idea to the group in the same way as he did to their accountant.

I’m not aware of public statements from any of the Beatles commenting specifically on the financial dimensions of the proposed Greek island purchase. But from what Hunter Davies, the group’s authorised biographer, wrote in The Beatles (1968), it appears that John Lennon at least was considering the possibility of the Beatles spending significant time in Greece. Davies writes that the “Greek island idea…greatly appealed to [Lennon] at the time”. He quotes Lennon as saying: “We’re all going to live there, perhaps forever, just coming home for visits. Or it might just be six months a year.”

Davies adds that the Greek [island] idea “even got to the stage of trying to work out what to do about [John’s son] Julian and his schooling.” He writes:

“He could go to school in Greece, [Lennon] told [his then wife] Cyn, who was obviously much more realistic about the problem than John. ‘What’s wrong with that? He’d just spend six months of the year there and the rest here at his English school.”

In line with these comments, the Greek journalist Labis Tsirigotakis, who reported on the Beatles’ visit to Greece in 1967 at the time, recently told the Guardian newspaper that John Lennon told him that the Beatles were considering buying a Greek island where they could live for half the year.

And in the 1995 TV documentary The Beatles Anthology, George Harrison appears to allude to the group’s wider financial situation with his comment (my italics) that “somebody had said you should invest some money, and we thought ‘well, let’s buy an island’”.

Via their representatives, I have asked Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr if they want to comment on the financial dimensions of the Beatles’ plans to buy a Greek island - including whether it was intended that the group would settle in Greece, and to what extent the plans were financially driven. I have not received a response from either.

The Beatles’s island purchase plans were being made at a time when a general restructure of their business and financial affairs was being planned. And if the group had gone ahead with the plans, it would naturally have had some implications for their financial circumstances. In the end, though, they didn’t – so perhaps we’ll never know exactly what these were expected to be.

Read more:

Lord Goodman: Lawyer to the Beatles - and the prime minister

Actor, architect, soldier…spy? The intriguing inner circle of Alexis Mardas

Where was the Greek island the Beatles wanted? The evidence