4. From London's summer of love to Greece’s military dictatorship

The Beatles visited Greece at a time when some prominent voices were calling for the country to be shunned

Read more:

Lord Goodman: Lawyer to the Beatles - and the prime minister

Actor, architect, soldier…spy? The intriguing inner circle of Alexis Mardas

Where was the Greek island the Beatles wanted? The evidence

On 16 July 1967, in the week before the Beatles' trip to Greece, the air of London's Hyde Park was "heavy with the smell of burning joss sticks", reported the Daily Telegraph, as more than 5,000 people gathered for a rally in support of legalising cannabis. The Times described the behaviour of some “flower children” at the event:

“Dressed in brilliant colours, some with their faces painted in vivid hues, they sat on the grass in the sunshine and preached the 'hippy' philosophy of absolute love, gentleness and kindness to astonished strollers. From time to time they pelted the police with flowers, blew bubbles, burnt incense, and tinkled the little bells that many of them wear round their necks.”

The Beatles openly supported this cause, at a time when someone could be imprisoned for months for possessing the drug. On 24 July - along with a range of prominent figures from the arts, the media, science and medicine - they put their names to a full-page advertisement in the Times arguing that "the law against marijuana is immoral in principle and unworkable in practice". The Beatles also contributed significantly to the cost of running the ad. On the day of its publication, though, they had already flown out of the UK for a country where the political situation was very different.

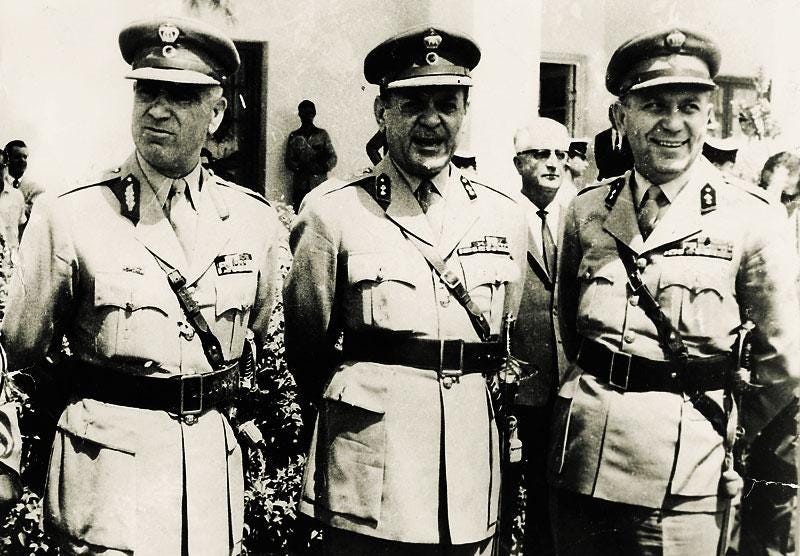

A few months earlier, Greece had been taken over by a “crude military dictatorship”, as a Times leader article described the regime1. In the early morning of 21 April, tanks rolled into the streets of Athens as a military junta led by a trio of two colonels and a brigadier staged a successful coup. The new regime immediately curtailed civil liberties and broke with democratic norms, detaining thousands of political prisoners.

News of the coup was splashed on the front page of British newspapers such as the Guardian, the Times and the Daily Telegraph, whose headline on 22 April declared ‘Martial law order in Greece’. The junta’s actions continued to receive prominent coverage in the British and US media over the following days and months – some of which is collected in King’s College London’s Modern Greek Archive.

Two days after the coup for example, the Observer reported that the junta had arrested more than 8,000 political leaders and ‘known leftists’ and was holding them in military detention centres. The next day, the New York Times told its readers that the regime had immediately suspended 11 articles of the country's constitution, giving itself the right to make arrests without warrant and detain people indefinitely for political crimes. The colonels also banned indoor meetings and censored the press.

The coup came after years of political upheaval in Greece, and the regime claimed that its authoritarianism was necessary to save the country from communism. In an early press conference, the Greek government’s de facto leader Georgios Papadopoulos described his country as a patient who needed to be strapped to the operating table in order to undergo surgery.

The regime sought to enforce a traditional morality, banning miniskirts for girls and long hair for boys. In many ways it defined itself against the counterculture that was emerging in other countries. A Sunday Times report by the journalist Richard West on 11 June described a young Australian man in Athens being questioned by a police officer about the length of his hair. “He made him stand up and then turn round, he tugged at a lock of hair on the neck and then took the offender’s name, age and address.”

While Greece used to be favoured by bohemian types, wrote West, "since the coup the Bohemians have departed and with them most of the beards and long thatches of hair… One would not normally judge a regime by its attitude to long hair and beards and other trifles, except that this regime is obsessed by such trifles.”

West characterised the mentality of the junta as “rather like that of those bloodthirsty and boring ‘saloon bar majors’ one meets often in England”. So it’s perhaps unsurprising that it soon clashed with some of the country’s most well-known cultural figureheads. The work of the composer and former member of parliament Mikis Theodorakis, who wrote the music for the hit 1964 film Zorba the Greek, was banned because of his left-wing views and activism. In July, the Times reported that a 23 year old woman had been "sent for court martial for playing Theodorakis records in her Athens flat".

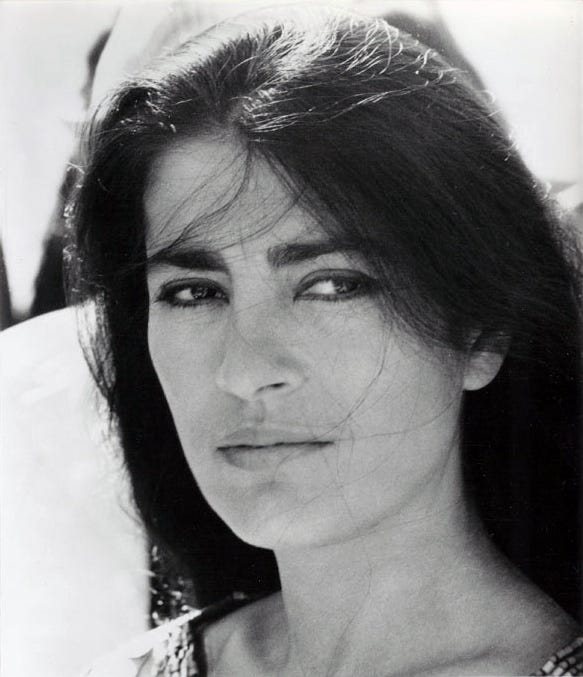

Another to fall foul of the colonels was the Greek actress Melina Mercouri. On 12 July she was stripped of her citizenship after she criticised the junta in television interviews in the US, telling viewers not to go on holiday to Greece. Mercouri called Stylianos Pattakos, one of the junta’s leaders, "a fascist”, saying he was welcome to make her into a “Joan of Arc" figure. Her sentiments were supported the following week by another Greek actress – Irene Papas, a star of Zorba the Greek – who called for a "cultural boycott" of the junta and “a firm, uncompromising stand against the Fourth Reich in Greece”2.

Condemnation in the UK

One organisation which shunned Greece was the British Musicians' Union. A boycott of Greece by the union led to two performances by the English Chamber Orchestra scheduled for the Athens festival in August being cancelled.

Greece’s new government was also targeted by various other protests and campaigns within the UK. A week after the coup, 42 people were arrested after more than 100 demonstrators “stormed into the Greek Embassy in London”, as the Times front page reported the next day. They “rampaged around the embassy offices and private quarters” for nearly an hour, set up public address equipment on the balcony and broadcast messages of sympathy to political prisoners in Athens via the radio transmitter.

The media continued to cover criminal proceedings against those arrested in this protest, and published numerous letters about the regime generally. On 8 May, several eminent cultural figures, including the classical scholar CM Bowra, the philosopher AJ Ayer, and critic Kenneth Tynan wrote to The Times to express their "deeply felt horror", saying that "the influence of the [British] government should immediately be directed against the prolongation of the dictatorial regime and against the threat of executions and summary courts martial". And on 29 July ten arts luminaries including the actress Vanessa Redgrave and writer John Le Carré wrote a letter to the same newspaper saying:

“We...urge, as artists and as citizens, that the present Greek regime should be actively boycotted by all who find its policies of censorship and coercion repugnant; and we wish to make clear our own intention of doing so. We will not support this regime economically, by spending our money on holidays in Greece. And we will not support its pretensions to respectability by taking part in its festivals or any other cultural manifestations.”

Such views were by no means limited to the hard left or the cultural sphere. There were some people who called for more understanding towards the junta. But the historian Konstantina Marankgou writes that an idealised view of Greece as a “bastion of democracy” helped fuel a “widespread expression of public revulsion” at the coup in Britain3.

In a Daily Mail column on 20 July, journalist Anne Scott-James wrote that she had cancelled her holiday in Greece this year due to the colonels’ “crassness”:

“I won’t go until the brutal censorship of arts and Press are lifted. This may be illogical. I’ve travelled in Russia, Spain, Portugal and many other illiberal countries and enjoyed myself. But to the Greeks politics are the breath of life…

I don’t like the regime. It’s unworthy of that splendid country. And like many who feel an emotional involvement with Greece, I shall this year abstain.”

These debates were taking place as the Beatles made their plans for an island retreat and visited Greece. On the face of it, the country doesn’t seem the most obvious destination for the group in their psychedelic pomp. The only comment I’m aware of from any of the Beatles on Greece’s politics at this time came from John Lennon, who told Hunter Davies (for his 1968 authorised biography of the group):

"I'm not worried about the political situation in Greece, as long as it doesn't affect us. I don't care if the government is all fascist, or communist, I don't care. They're all as bad as here, worse, most of them."

Barry Miles, a friend of the group, told the author Peter Doggett4 he was “horrified” by the Beatles’ stance, saying: “As I remember it, Paul was faintly embarrassed by it all, but John wasn’t concerned. As far as I can gather, the entire trip to Greece was just a haze of LSD, though. None of them really knew where the hell they were.”

I’ve asked representatives of Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr if they’d like to comment on this matter. To me, Miles’ recollection of the situation sounds plausible. But it doesn’t explain another puzzling question: why the “bloodthirsty and boring” colonels would want the Beatles to visit Greece anyway. So why did the trip happen at all? One key influence was the group’s Greek friend Alexis Mardas – more about him soon.

Read more:

Lord Goodman: Lawyer to the Beatles - and the prime minister

Actor, architect, soldier…spy? The intriguing inner circle of Alexis Mardas

Where was the Greek island the Beatles wanted? The evidence

15 July 1967

New York Times, 20 July 1967

In her 2019 book Greece, Britain and the Colonels 1967-1974

Quoted in Doggett’s 2007 book, There’s a Riot Going On